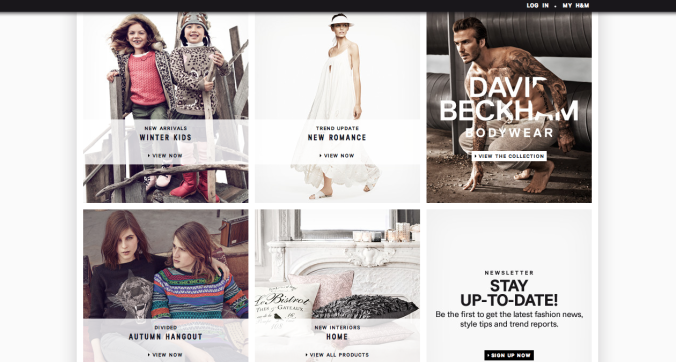

Within my community, a large Swedish chain store opened that is responsible for the advertising above. It took over one of the pivotal buildings for contemporary local designers in the last 10 years. Before the change, it house more than 30 businesses for local designers and became a fashion mecca, however in the last year, they were forced to close their doors for the flagship store of mass-produced crap (excuse my language, but this is something I refuse to agree with).

Last year the Rana Plaza building, housing factories making textiles for many large companies, including this one, collapsed, devastating the community. Their unethical practices and the skewed factory conditions have become widely known.

Despite their mass production, the company now claims to be working towards ethical and environmental standards, raising labour costs, and developing low-waste solutions to production. This article however, claims otherwise. It highlights the problems still associated with the big-business.

What we cannot excuse is, the issue Leonard raises in The Story of Stuff: What about the waste post-consumption? That 99% of products that are non-functioning 6 months after purchasing. My friends and I shopped at H&M, when we were overseas a few years ago. We bought basic, “essential items” – T-shirts, socks etc. Within approximately 5 washes they had lost their shape, colour, texture, and therefor style. What is their solution? Buy more! The socks were $3, why wouldn’t you just replace them? Instead of buying a shirt that would last me 5 years, I bought one that would last me 5 weeks that I could replace because it was cheap. This is consumer culture rearing it’s ugly head. And where did the old T-shirt go? In the bin… WASTE.

So what can you do? What are the solutions? DON’T SUPPORT MASS-PRODUCTION. Where possible, where your pocket allows, support local business. Instead of buying a plain white T-shirt from a big business, buy one from a local or ethical designer. It’s more expensive, yes. What if your pocket doesn’t allow for this? Shop at the op-shop. Second hand stores exemplify sustainability. It liberates people less fortunate, but also supports recycling, reusing, and reduces waste. When purchasing, look for quality, rather than price. Look at the material, where it was made, the stitching. Inform yourself and think about your choices and buy smart.

References:

Wells, R. (2013, September 4).Retail giant H&M to open at GPO. The Age. Retrieved from http://www.theage.com.au/

Ali Manik, J. and Yardley, J. (2013, April 24) Building Collapse in Bangladesh Leaves Scores Dead. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/

Siegle, L. (2012, April 8)Is H&M the new home of ethical fashion? The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/